Joumana Khatib

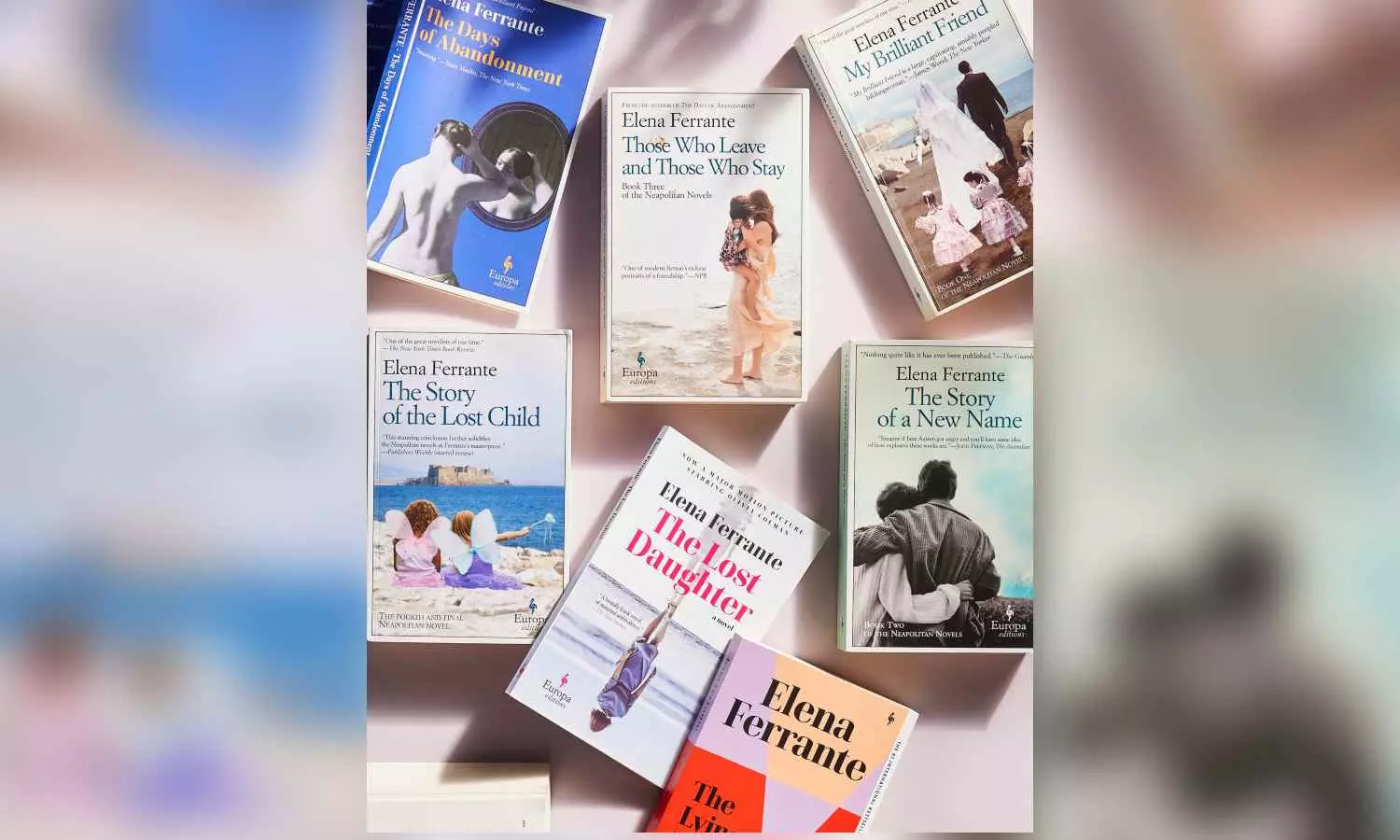

Seemingly overnight, Elena Ferrante — or rather, the novelist writing as Elena Ferrante — found worldwide acclaim. Her novels were everywhere: You couldn’t swing a tote bag without spotting one of her pastel-hued paperbacks on the subway, at the beach, in the airport. The four novels that make up the Neapolitan quartet rocketed her to fame. Beginning with “My Brilliant Friend” in 2011, the books, which include “The Story of a New Name” (2013), “Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay” (2014) and “The Story of the Lost Child” (2015), chart the lifelong, charged friendship between two women in postwar Naples, Italy.

Readers appreciated the nuanced relationship between the main characters, Lenù and Lila, a delicate mixture of love, jealousy and abiding loyalty. Critics zeroed in on Ferrante’s intimate attention to women’s lives, both in the Neapolitan novels and in her other books, which many writers of her generation had not considered subjects of literary merit.

But as her star soared, fans devoted to Ferrante and her books confronted a stubborn question: Who is Elena Ferrante, really? Ferrante has been publishing for over 30 years, and adopted her alias with her 1992 debut, “L’amore molesto” (later released in English as “Troubling Love”). With the appearance of the Neapolitan quartet, “Ferrante fever” began to spread, particularly in the United States, where literature in translation makes up a small fraction of popular fiction.

Ferrante has revealed some personal details over the years, claiming that she grew up in Naples, the daughter of a seamstress. She has implied that she is a mother, and married. Still, she has admitted to fudging the truth “when necessary to shield my person, feelings, pressures.” The initial reason for her anonymity, she told her editors in an interview published by The Paris Review in 2015, was shyness: “I was frightened at the thought of having to come out of my shell.” But as she continued to publish, her justifications for shielding her identity became artistic and philosophical as well.

Ferrante is private, but is by no means a recluse. For a year, she had a column in The Guardian, and she also wrote for Italian newspapers. A book of her nonfiction, “Frantumaglia,” includes biographical information about Ferrante and extensive correspondence between her and journalists. In interviews, she has regularly reflected on her own work — her influences, motivations, states of mind — and, however paradoxically, her reasons for remaining hidden.

Ferrante and her longtime editor, Sandra Ozzola, have a close rapport. Ozzola and Sandro Ferri head the Italian publishing house Edizioni E/O, which has released Ferrante’s work for decades; by all accounts Ozzola is Ferrante’s gatekeeper. Ozzola did not respond to a request for comment. Europa Editions, which publishes Ferrante’s work in the United States, declined to make Ferrante available for an interview.

Michael Reynolds, the editor in chief of Europa, doesn’t know who she really is, nor does he have a desire to find out. “I am completely uninterested, and have been from Day No. 1,” he said in a recent phone interview. “No one cared for 10 years,” he recalled of the interest in Ferrante’s personal life. And when interest surged, it was “a media creation — no offense,” he said, wryly. “It’s a great story for the media, but in most cases, for a large number of readers, they’re more interested in the books.”

Her identity is a secret even to her longtime English translator, Ann Goldstein, who has helped vault Ferrante to worldwide popularity. Though they have emailed directly fewer than a handful of times in the nearly 20 years that Goldstein has handled Ferrante’s work, the majority of their correspondence goes through Ozzola. “I’ve translated a lot of dead authors, so I’m used to having to figure it out myself,” Goldstein said.